Photo by Clark Tibbs on Unsplash

Startup Thinking

I have a firm leg in the doom and gloom camp. My friends alternate between sending images of the burning Amazon and pictures of Amazon — the company, not the lungs of the planet — replacing all jobs with robots. Not that I mind; all that misery gives my optimist brain something to push against.

So when someone asks me if startups can save the world, my first response is: of course. Five seconds later, I change my mind to: you must be kidding! Back and forth, here’s how I argue with myself:

Me: How can startups change the world? They are tiny and the world’s problems are huge!

Myself: They start small, but they don’t have to stay small! Remember what Steve Blank said: “a startup is an organization formed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model.” Repeat after me: scalable, scalable, scalable.

Me: Yes, but when they become bigger, they are no different from the other Death Star corporations sucking the life out of the planet.

Myself: but we can invent a new type of startup that’s less Death Star and more Jedi Knight. Startups don’t have to be about profits any more than factories have to manufacture cloth and nothing else.

and so it goes.

There’s something about how startups harness psychological energy and navigate uncertainty that appeals to me, and increasingly, we have data that tells us what works when people come together for a common purpose. Why not use it to make the world a better place?

To paraphrase a man who first gave me hope and then disappointed me: yes we can.

It’s never been easier to go from idea to implementation to turn a profit. Everything from Y-Combinator to my neighborhood angel investor are waiting to turn blood, sweat and tears into ?. Unfortunately, saving the world is mostly not a matter of ?. It’s about putting people and planet before profits. Here are three of my favorite world-savers:

Not a single businessman in that panorama. They were all politicians. That’s cuz politics is the most important method through which we have saved the world in the last two hundred years — both liberators and dictators have been politicians.

Note: none of them is a woman. I apologize for that snub to half the earth’s population. Patriarchy inserts itself into the STW business.

While the US doesn’t encourage political startups, i.e., new political parties, it’s common in other parts of the world for parties to be formed. Especially when there are classes of people whose needs aren’t being met by any of their current choices. Sometimes those new parties win elections and become political corporations and even one party states. Political monopolies suck even more than business monopolies.

The good news is there are more forms of political entrepreneurship than we can imagine, so why only political parties, why not other political startups? What about international political associations around global topics such as climate change — do we really think such wicked problems can be solved by middle aged women and men sitting in the U.N General Assembly? If you believe so, I have a couple of bridges I want to sell you.

I will tell you why like startups. They are the most robust institution we have devised for collective action amidst uncertainty. Corporations and governments are good at delivering solutions that work, but only startups are good at finding out what works in the first place. How will Indian farmers handle shorter, more intense monsoons? I don’t know, but I bet there’s a startup somewhere that will come up with a good idea.

Please stop thinking a startup is only about money.

We should divorce the idea of the startup from its capitalist origins, just as factories arose in the capitalist world but spread to societies where the government ran all forms of production. I am not saying one’s better than the other, just that startups and factories are flexible institutions capable of doing any number of different things.

I am a 100% certain that the future of the human species is bursting with uncertainty — pun intended. We have to become adept at navigating chaos and for that “Startup thinking” is an essential quality. Only if it combines politics, engineering and design though.

Forestree

I went to an engineering school but I didn’t study engineering. In fact, I have stayed away from engineering my entire life despite being a geek. Cooking, yes. Sports, yes. Maker spaces: of course. But not engineering.

That’s because engineering struck me — perhaps wrongly — as being focused on the small picture, of making this widget in front of me work without caring about its connection to the wider world and damn the consequences. It wasn’t a discipline that encouraged a philosophical bent of mind. Engineering has undoubtedly changed the world, but it has done so without taking responsibility for that change.

In contrast, politics always struck me as being closely tied to philosophy: or to paraphrase Marx: we don’t want to study the world, but to change it. And there’s no shortage of political writing as to why we should change the world this way rather than that way. Politics, however disagreeable, takes responsibility for changing the world, which is why the metaphorical levers of politics were better suited to my theory of change than the mechanical levers of engineering.

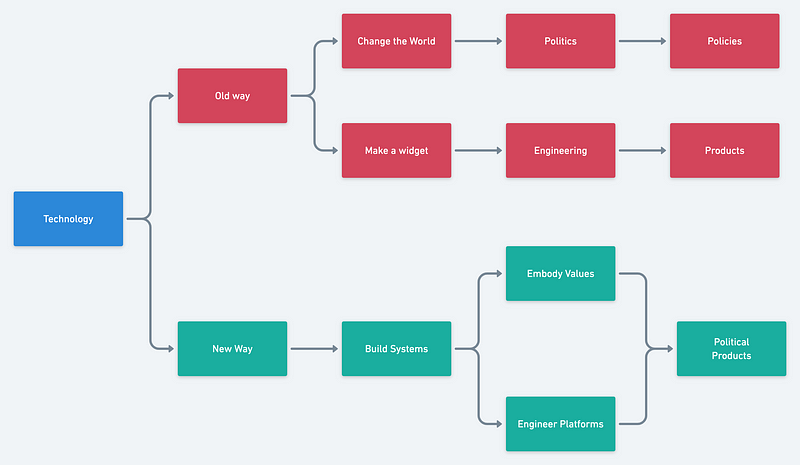

Of late, I have been feeling that the division between politics and engineering is disappearing. Both are technologies that create human artifacts in response to individual and collective needs. Until recently, it was easier to encode big-picture goals in political technology than in engineering technology. For example:

Do you think democracies should have a separation of powers those creating policy and those enacting it? Solution: create separate institutions for the two purposes.

Today, similar decisions are being made in engineering technology: if you want to create a platform in which the platform owner doesn’t have an undue advantage vis-a-vis other participants? Make sure their business development wing only has access to the same data as any other business using the site. API design can encode ethical features and value judgments in a manner unthinkable fifty years ago.

Technology, old and new

The reason politics and engineering are coming together is code — and I use that computing phrase in the broadest sense of the term. Political technology has always been based on text: constitutions, policy briefs, white papers and such. Engineering technology has been based on things: steam engines and marble tiles. Code functions both as text and as thing. That’s a huge transition in how we change the world. We are just scratching the surface of that revolution.

That realization got me thinking about problems that should be solved simultaneously as engineering products and political policy, with solutions exhibiting a combination of good design, good data and deep concern for social implications. Technology that pays attention to the forest and the trees. I am on the lookout for such “forestrees.”

Here’s the first.

Photographer: Ben Hershey | Source: Unsplash

Concussion Detection

Halfway through the first game of the season on Saturday, my daughter took a soccer ball to the face. She continued playing for a couple more minutes before her nose started bleeding when she had to leave the field and couldn’t play the rest of the game. This being the United States, a trainer checked her out and suggested she might have the mildest of concussions, which meant no more games that weekend. Fortunately, she was fine the next morning and ended up playing on Sunday.

I love my daughter more than anything in the universe but this essay isn’t about her. It’s about how she was assessed for a potential concussion. She was checked by trainers three times on Saturday and Sunday. I noticed that on all three occasions, the trainer whipped out her phone and used the phone camera to make an assessment.

There are a couple of concussion assessment apps in the iOS app store but none of them are fancy — they are just a list of protocols to follow, including making the player stand on one foot, move their arms in set patterns and so on. Looks quite crude if you ask me, though arguably optimized for assessment by a young person with little experience.

Photographer: Ishan @seefromthesky | Source: Unsplash

Eye Movements

I asked myself if we have better signals for concussion.

What about eye movements or other neuromuscular signatures? A quick google search lead me to this paper which says that disconjugate eye movements (i.e., when the two eyes don’t move in synchrony) are present in more than 90% of concussion and blast victims. I am not sure if trainers have the medical training to detect disconjugate eyes, especially if lighting conditions aren’t good. Disconjucation detection (DCD for short) might be too hard for untrained human beings.

But we are forgetting that camera. It seems underutilized — I saw the trainers shining it into my daughter’s eyes one eye at a time. DCD needs to process the signal from both eyes at once for it to work — after all, we want to find out if they moving in unison.

Let’s eliminate what I think of as the easy case — in the case of severe concussion, the two eyes are more likely to be completely out of sync. A severe concussion is likely to be a result of a major collision either on a sports field or in an automobile. Those aren’t the obvious cases I am thinking about, since they will be referred to emergency care right away. Concussions from a minor incident on a children’s playground or from an elderly person falling in a bathroom are harder problems to solve, and the solution has to be be in your pocket.

Phone is all we got.

Photographer: Alice Donovan Rouse | Source: Unsplash

Optical Solutions

An optical problem has to be solved first, a robust method for detecting eye movements from both eyes. There has to be a way of sweeping a phone camera in front of someone’s eyes so that it picks up the eye movement signals from both eyes at once. It’s a technical challenge because the signal is masked by an enormous amount of noise: jitter because of shaky hands, changing reflection patterns because of blinking eyes and head movements, changes in light sources if clouds block the sun and so on.

Fortunately, we have a clean separation of movements:

There’s the relatively smooth movement of my arm as I scan the camera in front of your eyes. Assuming that the light source from my phone camera is the only light that’s changing in intensity — ambient light from the sun or artificial lighting being assumed constant — the light reflected back from your eyes is going to be a smooth function of my hand movements. Further, smartphones now have motion sensors so we can use hardware to detect and filter out movements initiated by the person holding the camera.

There’s the jerky movement of your eyes as they saccade and change focus, and every time that happens, there’s a sharp change in light intensity. There’s are also the jerky movements of my eyes blinking, but that happens at a slower rate than eye movements and is an up and down movement while saccades have two degrees of freedom.

I am betting on a relatively clean separation of signal (eye movements) from noise (the camera movement, her head movements, blinks etc). In short, while there are genuine technical difficulties, I am reasonably confident that the signal detection problem can be solved. But once we have the two channel signal — one channel for each eye — we are left with an inference problem: how do I know when a signal indicates concussion?

Inferring Concussion

The simplest kind of processing that can be done on the two channel signal is a summary statistic, such as the correlation between the two channels. Disconjugate eyes will have lower correlation between the two channels than normal ones. If we are happy with a simple diagnostic, this is all we need to do: set a concussion threshold and slot anyone who meets that threshold for medical intervention.

That, by the way, is the nature of most medical interventions based on bodily indicators. If I go to my doctor’s office with a test result and if my blood pressure, blood sugar or cholesterol is above a certain threshold, they will likely talk to me about further testing. If the statistic is in a band that’s not too low or or too high, they will talk to me about my diet and exercise regime and suggest changes if necessary. Otherwise, the machine’s working as it should and I go home happy.

But we can do better than that today, can’t we?

There are several problems with the simple diagnostic. Let me mention three:

It might lead to false positives if the threshold is too low and false negatives if it’s too high. For example, if I have strabismus, I am likely to trigger a false positive.

It’s not personalized: My body might disconjunct at a lower contact threshold than yours. Even if there’s momentary disconjunction, your body might recover more quickly from it than mine. If disconjunction is a transient signal, how do we know when it’s a reliable indicator of concussion?

More generally, signs of concussion might be hidden in higher-order statistics instead of simple correlations. If so, noise will prevent us from extracting those higher-order statistics from a single observation.

The alternative is to go for a top-down approach based on extensive data collection. If I collect my eye movement data over time, the system will learn the typical conjunction between my eyes and how that changes with exertion, time of the day and other variables. With a robust data set like that in the background, we can be much more confident about when a genuine concussion is the cause of disjunction. Instead of creating a simple summary statistic and basing our diagnosis on just that alone, we can create a Bayesian concussion detector that answers the question:

How likely is it that X has a concussion based on the record of her eye-movements?

Detection accuracy will obviously improve if the system has access to eye movement data of thousands of soccer playing children. Having that data in the background will also help diagnose whether my child’s post-concussion recovery is on track.

Where is her disconjunction one week post concussion relative to the population average?

Should we be looking at a more intensive check-up?

Every trip to the emergency room costs money and leads to higher insurance premiums. We want to base any decision to send a child to an emergency room on the most robust data we have on hand. Longitudinal data is better than sporadic data.

Even better, longitudinal collection of eye movements across a population will be helpful in any number of other situations. Dyslexia immediately comes to mind. We know the eye movement of dyslexic children are different from eye movements in children who read normally. The earlier we detect those pattern differences the better, especially if dyslexia is (partially) a learned eye-movement pattern than a higher-order cognitive disorder.

Not that you need convincing, but there’s no shortage of advances in health and wellbeing that need repositories of biological data, from eye-movements to cholesterol levels. But, and there’s a HUGE but: the possibility of exploitation, control and oppression is so much greater when data are collected and made available to corporations and governments. In order to avoid big brother, platform design should encode a “fair use” policy with respect to all the data hosted on their premises.

To put in crude terms, whose data is it?

First: who will create such a data set and if I create that set, do I own it? Let’s start with the latter — that the creator of the data set is the owner, which is the current default. Since data is supposedly the new oil, it’s no surprise there’s a rush to capture as many valuable data sets in your hands as possible, leading to all kinds of problems. Search monopolies are bad enough, but we certainly don’t want health data monopolies.

Let’s say Startup A raises a ton of VC money and creates a comprehensive eye-movement database whose API used by Startup B for concussion detection and Startup C for dyslexia monitoring. Two years down the road, Startup A enters its own concussion detection app, competing directly with Startup B. What’s B to do? How does an application company compete with a platform company?

There might be a programmatic solution — as I had mentioned in the introduction, we can design APIs that prevent the business development side of Startup A from having access to data that the users (Startups B and C in this case) have access to. But can API modularity be enforced without regulation?

I doubt it.

Also, platforms keep evolving. Imagine that Startup A discovers that while the market for concussion and dyslexia apps is individual parents and teams, hospitals and HMOs are an ideal market for the platform as a whole. What does A do? Make an offer to B and C that they can’t refuse? Enter into a complicated revenue sharing model?

Platform monopolies are even more entrenched than widget monopolies — the dominance of the FAANG platforms being a case in point. Despite the popular slogan, data isn’t oil; it’s not a resource that disappears after being used once. Instead, it gets more valuable with time and accretes more uses.

Which makes data prone to platform monopolies since platforms are designed for current as well as future uses — once you list all the books in the world, you can sell them yourself, offer space for others to sell, convert them into ebooks sold by your company or direct the customer to a competing book that has a higher rating on your own system of ratings. I can’t see a future in which privatized data is good for anyone besides the monopolist.

How will that work out in healthcare? If we want to avoid monopolization, we should keep the data open, say through the creation of a platform commons. That leads to another challenge: who is going to pay for such a platform? It’s not like creating an open database of cat videos — the regulatory demands of collecting and storing biological data will make their platforms prohibitively expensive for your typical non-profit.

Is the only financially and politically viable solution is to socialize the data? Which is to say, governments pay for the creation and maintenance of health data repositories and own the platform. Governments having ultimate ownership has its own challenges, especially in countries where citizens don’t have political control over what happens to their data. Which, to be honest, is the case in most liberal democracies let alone authoritarian regimes.

Plus, what do you think are the chances of a government creating a high-quality platform? Might be possible in a small and rich country like Sweden, but the U.S health care debacle suggests that creating universal health data systems in a large and diverse nation is an incredibly hard problem to solve.

What is to be done?

I have a utopian answer: data should be a universal resource like time. Clocks became important after the industrial revolution and transcontinental railroads, but there were thousands of time-measures in the early days of mechanical time-keeping. As this article says,

When the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific Railroad formed the Pacific Railroad, later called the transcontinental railroad, more than 8,000 towns were using their own local time and over 53,000 miles of track had been laid across the United States. Railroad managers and supervisors well understood the problems caused by so many discrepancies in time keeping.

There could have been many ways of solving the problem of time standardization:

Let railroad mergers dictate time mergers so that at the end of the process there are a few private time companies in the world that own my time and your time.

Let the government own the time — and tax you for owning a watch?

Create an international standard for time that no one owns or even thinks of owning.

Aren’t we glad we chose the third option — can you imagine time being owned by Acme corp instead of being an international standard? Why can’t we do that with data? Why can’t we have universal, secure data systems that aren’t owned by anyone and enable any number of products?

One international data standard that stores and maintains all the important data in the world. Cue photos of smiling children and dogs playing in the sunshine.

You may not agree with my solution — feel free to leave yours in the comments, but I hope you’re convinced that:

It’s hard to design platforms that serve our needs today and in the future.

We need both engineering and political technologies to design such platforms.

Now for the philosophical climax of today’s program…

Octopus Politics

I can’t end an essay about creating data driven systems without a nod to data dystopias. There are the obvious dangers: hackers stealing your medical records and blackmailing you, insurers refusing service because of genetic predispositions, governments denying treatment to political dissidents and so on. While they are important worries — it would be a disaster if a hacker changed your baseline heart rate during a cardiac treatment — but in my view they are problems of the past, based on the model of the “all-seeing eye” or the panopticon.

There’s a difference between the world of meager data and the world of rich data.

A world of meager data is one where I don’t know what’s going on in your head. We are atomic individuals separated by infinite mental space. The all seeing eye assumes a uniform space occupied by atomic souls who are mostly like each other. In that world, the panopticon appears either as a blessing or as a nightmare — blessing if you’re the religious type and like the idea of a divinity knowing every thought that crosses your mind, and a nightmare because you’re the cynical type that doesn’t want god or the government having access to your desires.

Note how both the blessings and the curses arise from the act of being “truly seen.”

In response, we created liberal democracies where the government knows some things about you but not too much, where insurance companies write policies based on the normal individual and where you have to be in prison or a totalitarian state to be completely exposed to the authorities. To summarize: meager data, health insurance and liberal democracy are a package that pleases many people much of the time.

I believe the world of rich data will be substantially different. It’s prime worry (or blessing!) will not be whether I am being truly seen, but whether there’s an I at all. There’s no reason why the Snapchat self and the iHealth self and the iVote self are the same self or even feel like being the same person. What if the experienced of a unified self is an artifact of history?

What if the reason you feel that you vote, you work and you play is because you live in a time when you have privileged access to your internal states — as Descartes famously thought — while others have limited and indirect access to those states?

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6laZ9ad-D54[/embed]

A useful way of thinking about technology is as an extension of our mental apparatus. Glasses are extensions of our visual system, hearing aids of the auditory system and equations of our conceptual capacities. But none of these do much computing. Imagine instead a third prosthetic arm that has as much computing as your peripheral nervous system — what do you think it will do your experience of the world? Or, for that matter, when data platforms are as good at predicting what you will do next as you can.

In that world we might feel less like human beings of the past and more like Octopi with eight arms, each one of whom has a mind of its own. Those arms usually act in unison but they don’t have to. Sometimes they clearly don’t. I don’t know what it feels like when arm 7 and arm 3 go to war against each other and I have no way of stopping the fight. I certainly don’t know what it’s like when arm 6 votes for Trump and arm 1 votes for Hillary.

Let me leave you with a final question: what will it be like to build a global society around a multiple selved creature?

I am not sure if there’s a startup creating the Octopus empire, but there should be one.